Victoria Road Trip - Some Assembly Required

"This can't be it,' I said, peering out of the windshield of my rented car. We were in a modest residential neighbourhood in Victoria, looking for Dino Lab, one of our first stops on a road trip from Vancouver to Vancouver Island.

"Sorry. Can't really help you,' said Phil, who was my passenger. Phil has been blind for the last 30 years, so I could see he had a point.

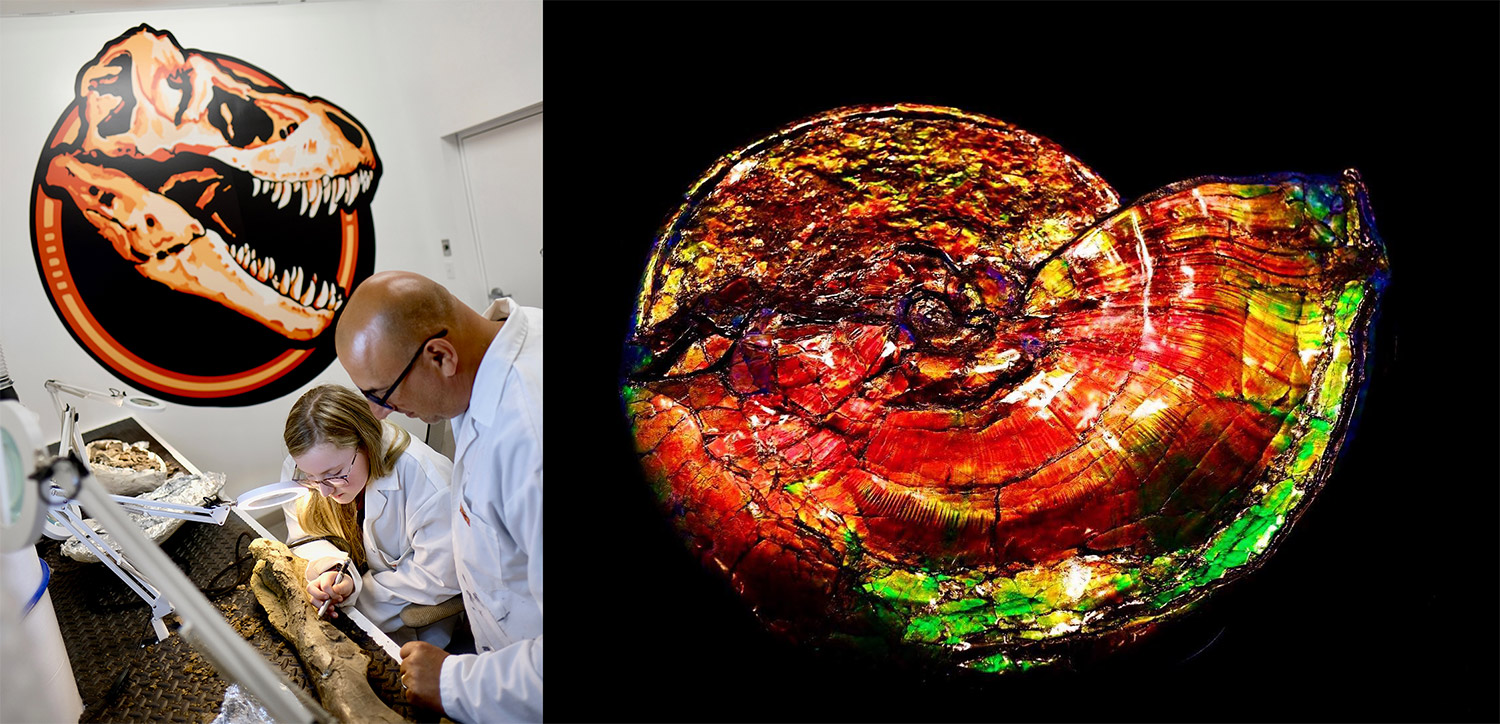

Then I spotted the Dino Lab emblem on a sign advertising several businesses at the head of a driveway. The driveway sloped down to what looked like a small parking lot bounded by several garage doors and the loading bay of a self-storage facility. Standing in the parking lot were several people who looked as if they, too, might be looking for Dino Lab, so I drove down the driveway to join them.

Inside the glass door to what could have been just about any retail business, we were greeted by our guide, Kathryn Abbott. Dino Lab's tours are limited to 10 people and are by appointment only. Abbott clearly has great knowledge of and enthusiasm for her subject. So much so that her forearm bears the tattoo of a spinosaurus skeleton.

Upon entering the exhibit area, the first thing you notice is a 40-foot-long skeleton of a T-Rex. It is the second-most-complete tyrannosaur skeleton in the world. Since this writing, it's left on a world tour and has been replaced by the assembled bones of another iconic dinosaur, triceratops.

Abbott begins the tour by asking each of us to name his or her favorite dinosaur.

Apparently, most people don't have a favorite dinosaur (hard to believe, I know). Everyone else on the tour says tyrannosaurus, mainly because, I'm guessing, it's the only dinosaur whose name they really know. And because the skeleton of one was pretty much breathing down their necks. Even dead for 65 million years, they're still a bit intimidating.

My favorite dinosaur has always been the triceratops. In the How and Why Wonder Book of Dinosaurs, (which was my introduction to the subject and pretty much my main source of knowledge of dinosaurs to this day) the depictions of Jurassic life always showed the tyrannosaurus with one clawed foot on triceratops' crested skull, trying to pin its head to the ground, probably demanding his lunch money.

But the triceratops, protected by his wonderful shield and lance-like horns, always fought back, usually goring the T-Rex in the belly. Triceratops may have been a peace-loving vegetarian, but he didn't take shit from anybody.

Abbott then directs our attention to the bully dinosaur, describing the origins of the tyrannosaur skeleton and explaining that the bones it is comprised of are all held to a steel "spine' by magnets. Hence, their ability to be detached and handled by the tourists.

Each of the fossils that have been prepared for us—ranging from a single tooth to long bones--is handed around the group while Kathryn tells some fascinating story about its origin or function. This is especially great for my friend, Phil, whose contact with much of the world is far more tactile than yours or mine. While he takes his turn running his hands over each of the artifacts, I do my best to supply visual captions for the hard of seeing.

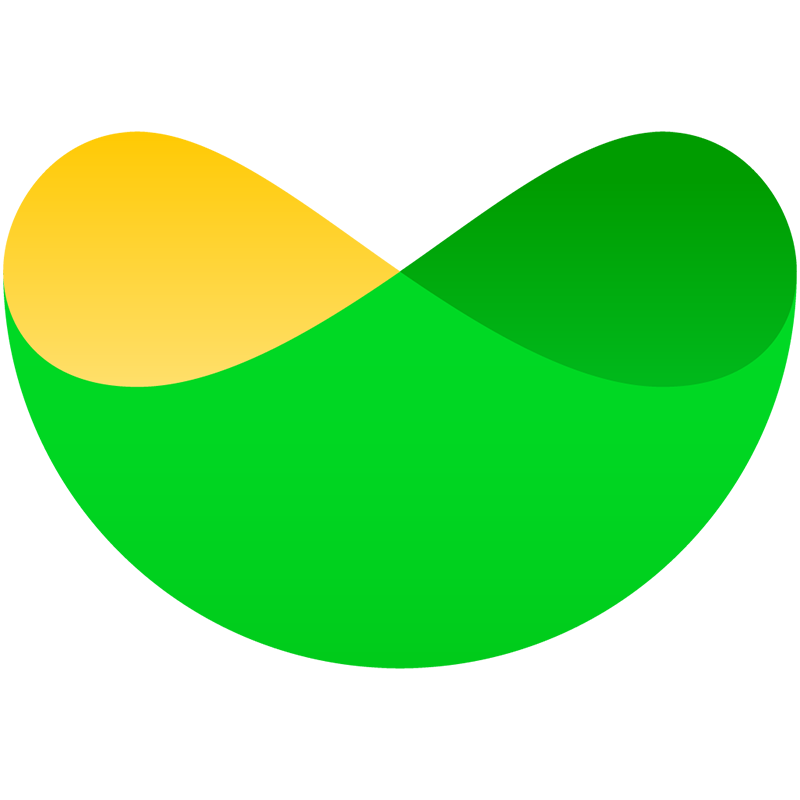

For some reason, I feel that this is especially necessary when describing the stunning, iridescent impression of an ammonite unearthed from the bearpaw geological formation in Alberta. The colors of the spiral shell are kaleidoscopic.

"It really is incredible,' I offer. "You should see the colors!'

"Yes, I should. Thanks for the reminder, Dave.'

To hold something that old in your hands, to know that it was once part of a living, breathing creature, is quite sobering. Although, technically, the original bone is long gone, rotted away. But almost every bit of it has gradually been replaced with far more durable minerals in exactly the form of the original. In other words, you're really holding a bone-shaped rock.

There are no interactive exhibits here. No virtual restorations. No information plaques or signage. There aren't even any animatronic dinosaurs! (Remember them?) These exhibits date back much further than that. The artifacts on display here are all at least tens of millions of years old, the real thing. And yet you and I, John Q. Public, can handle them!

That's because these are all fossils that originated on private lands in the United States. That's not quite true. They originated as dinosaurs living on pieces of continent that would eventually drift to what is now called North America where ultimately a country to be called the United States was founded. The difference between the U.S. and Canada (at least when it comes to fossils) is that in Canada, a fossil becomes the legal property of the government the moment someone excavates it. In America, it instantly becomes the property of Amazon.com, Inc.

Just kidding. Fossils in the United States belong to whoever owns the land where it was exhumed.

I said there are no "interactive' exhibits here—at least not in the sense of the computer and video kiosks so prevalent in modern public exhibits. But in fact, the Dino Lab tour is the most interactive experience imaginable. Not only do you get to handle the bones, you can ask any question you want of your guide, and she will answer it. Certainly, I couldn't stump her.

After our tour of the fossils, we're then taken to the lab for our second hands-on experience. Each of us takes a seat at a different station where we try our hand at fossil liberation. We use a large, buzzing pen (like a mini jackhammer) to carve more fossils from the host rock in which they are encased.

After about a half hour of careful grinding, we're told that our tour has come to an end and that it is time to make room for the next group. If nothing else, our brief time in the lab has given me a new appreciation of what an enormously painstaking and time-consuming task unearthing the skeleton of a full-sized dinosaur must be.

It's all over in about an hour-and-a-half, but I found it to be the best $40 I've spent in a long time. The tactile contact, the small group size and the full access to an incredibly enthusiastic expert make it an intimate experience. There are none of the buttons, screens and levers now common in so many museums designed primarily to keep visitors—particularly children--occupied more than informed. Partly because of that, I would recommend the Dino Lab experience mainly to people who already have some interest in dinosaurs or paleontology.

But who could fail to be interested in a world of giants that walked our Earth for a hundred million years, then vanished in a geologic flash—the only monuments to their existence left as stone hidden in stone and buried beneath our feet?

Some assembly required.

Comments

Of course, the Tyrrell museum is a feast for any fan of dinosaurs or paleontology. With its huge fossil collection and superb exhibits, it's definitely worth a trip to Drumheller. Dino Lab is a more low-key, intimate experience. And if you're looking for the answers to specific questions, much more efficient!

- December 16th, 2019

This is great! I had no idea Dino Lab existed. I wonder how the experience compares to Drumheller ...

- December 16th, 2019